Scientists studying the Colorado River are finding a quickly changing environment that’s reminiscent of a life lived before the Glen Canyon Dam.

By Zak Podmore | Photography by Francisco Kjolseth

Cataract Canyon • When Mike DeHoff began leading river trips in the early 1990s, there was little ambiguity about where the Colorado River ended and Lake Powell began.

DeHoff, who guided students on Outward Bound courses in southeastern Utah for over a decade, taught backcountry travel skills on the remote, winding flat water of the Green and Colorado rivers in Canyonlands National Park. Below the confluence of the two rivers, his students learned to navigate the challenging whitewater of Cataract, a series of 26 rapids culminating in the run’s three-part crux: the Big Drops.

When Lake Powell is filled or near capacity, as was the case through much of the 1980s and 1990s, the river current stopped just downstream of the drops, its muddy waters becoming a limpid blue reservoir as hundreds of millions of tons of sediment settled to the river bottom.

“I remember one day we were on this great trip [in the mid-1990s],” DeHoff said. “We were scouting Big Drop Three, looking downstream, and there were Jet Skis and a cabin cruiser sitting in the eddy. Jet Skis came running up, and someone was trying to play in some of the tail waves. It was just such a contrast.”

Scouting the Big Drops today, that scene is almost impossible to picture.

In July, Lake Powell hit its lowest level since it was first filled in the 1960s, with the water level 155 feet below its full pool elevation. If cabin cruiser owners can even find a way to launch on the boat ramps in Glen Canyon National Recreation area, most of which became unusable this summer, they’re restricted to a dwindling reservoir that now begins roughly 38 miles downstream of Big Drop Three.

As the Colorado carves a channel through the reservoir sediment, long-buried rapids have started to reemerge, side canyons are being scoured of mud, beaches are forming again, native plants are reestablishing themselves and habitat for threatened fish species may be expanding. For those who know the place well, the changes in this living laboratory are as constant as they are surprising.

DeHoff currently earns his living welding custom raft frames and equipment in Moab, but he still organizes river trips through a group he co-founded called the Returning Rapids Project. Instead of guiding teenagers on Outward Bound courses, however, his passengers are now more likely to include leading policymakers and water managers in the region, along with conservationists, historians and scientists.

The mission: to better understand what happens when a river, inundated for decades, begins to recover.

A circus of science

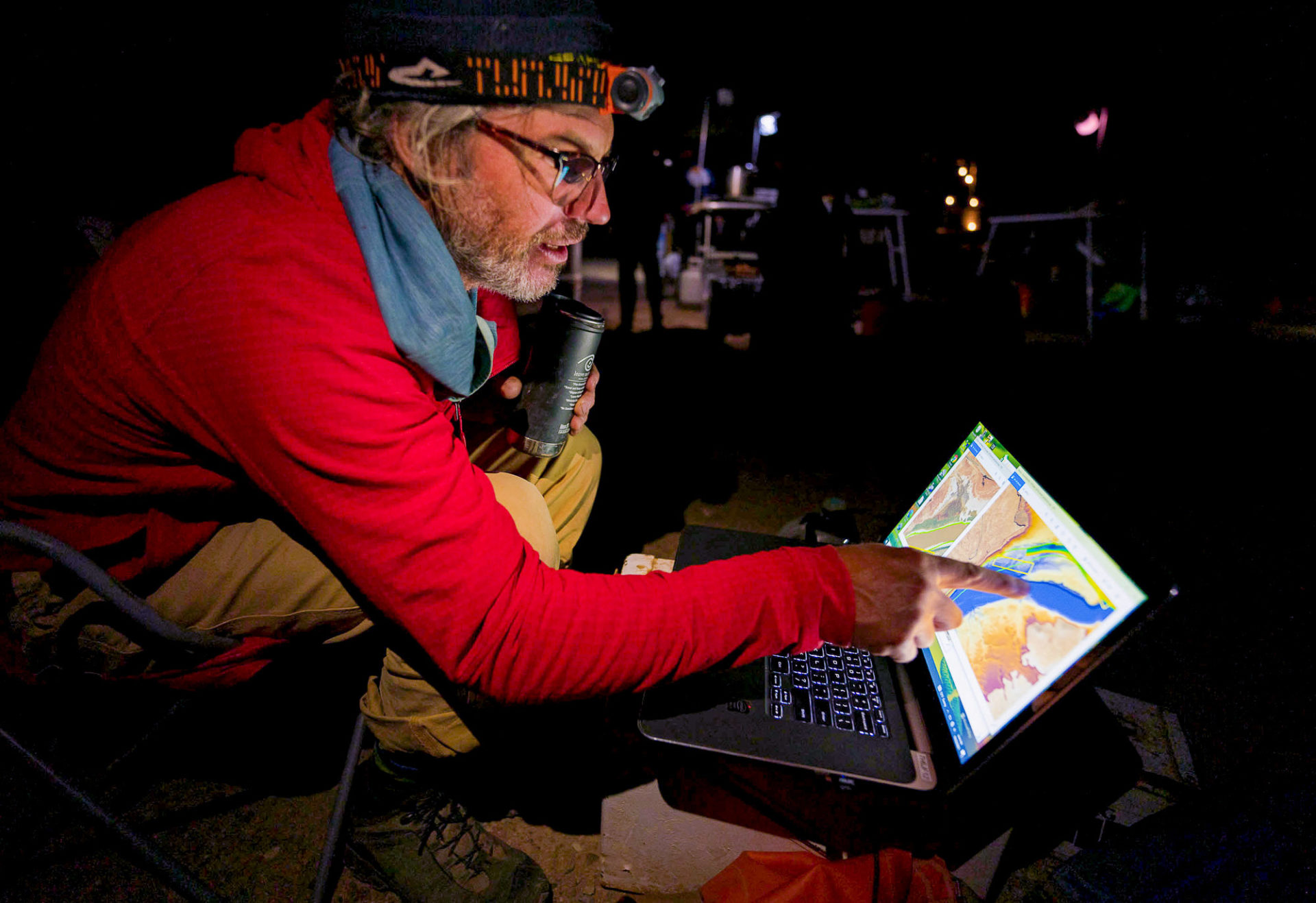

On a chilly morning last month, DeHoff gathered the 28 participants in the latest Returning Rapids Project trip beside the Colorado River just west of Moab. After outlining the schedule for the 96-mile trip from the Potash Boat Ramp to the North Wash takeout, DeHoff explained his role — he would serve as ringmaster for a floating circus of science.

Over the next seven days, the description proved apt. A grin rarely left DeHoff’s face as he helped coordinate the pods of university professors and government scientists who broke away from the group each morning to pursue their various research agendas.

A crew from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) used sonar equipment attached to a motorized raft to map the three-dimensional streambed topography, a logistically complicated process requiring GPS stations to be set up at various locations along the riverbanks. Other USGS employees collected water, soil and sand samples, while fisheries experts monitored populations of native humpback chub in the rapids of Cataract Canyon. Ecologists looked at the distribution of native plants and the growth of living biocrust on the exposed reservoir sediment.

Around the campfire at night, the typical river running tales of whitewater mishaps were interspersed with impromptu geology lessons, focused not on the millions of years of history represented in the canyon walls but the much more narrow geological record found in sediment banks in upper Lake Powell. Researchers swapped hypotheses and anecdotes about the constantly changing environment.

“DeHoff is sort of the prophet of Cataract Canyon, and I have joined his church,” laughed Brenda Bowen, director of the Global Change and Sustainability Center at the University of Utah, who is analyzing the chemical makeup of reservoir deposits. “He’s such a charismatic, thoughtful and gentle leader of this whole project. … He’s built this network of scientists who are really excited about what’s going on here.”

Bowen, a geology professor who studies how human activity is affecting landscape evolution, said that by bringing together scientists from numerous disciplines, the Returning Rapids Project is helping broaden researchers’ understanding of the ways low reservoir levels might impact human and ecosystem health.

Megadrought brings change

Although DeHoff is sometimes seen as the face of the organization, he is quick to list the many other people who have made the Returning Rapids Project possible. Foremost among them is Peter Lefebvre, a veteran river guide based in Moab.

Lefebvre first ran Cataract in 2002, a year many climatologists mark as the beginning of a new cycle of decreased snowfall, which has been described as a “megadrought” and the “new abnormal” by Science magazine. A decade later, he was running 15 to 20 trips down Cataract Canyon each year and noticing something new in the lower canyon on every trip.

“I had a lightbulb moment after watching ‘Chasing Ice,’ a movie about glaciers retreating,’’ he said. “I wanted to start trying to document all the change that was happening [in Cataract].”

When Lefebvre stopped by DeHoff’s shop in 2017 and asked for welding lessons, the pair struck up a friendship and the Returning Rapids Project was born.

Meanwhile, DeHoff’s wife, Meg Flynn, who happened to be working on a master’s degree in library science, helped the group find historic photos of pre-dam trips through Cataract that had been stored away in university archives.

Through repeat photography and with the help of other river runners, DeHoff and Lefebvre began to formalize their documentation of the dozen rapids and riffles below the Big Drops that had been filled with sediment and were now beginning to reemerge.

The effort slowly crystallized into a more ambitious project. Geologists with the USGS and Utah universities caught wind of the group’s efforts, and the Returning Rapids Project was granted special use permits from Canyonlands National Park to transport scientists through the canyon.

“It turned into this feedback loop where we’re getting more information from different angles,” Lefebvre said, “to document the restorative power of the river.”

Crisis and opportunity

For Jack Schmidt, a professor at Utah State University’s Center for Colorado River Studies, the research being conducted in lower Cataract Canyon could complicate political plans that are being made about how to best manage Lake Powell, the nation’s second-largest reservoir behind Lake Mead.

“The biggest management decision that lies ahead,” he said, “is what to do in the next wet spring runoff year, whenever that occurs.”

The business-as-usual approach, Schmidt continued, would be to refill the reservoir, but the research is helping add nuance to planning efforts by illuminating how reservoir levels could impact water and air quality, among other concerns.

“What are the valued ecological and recreational and archaeological and historical resources … below full pool elevation?” Schmidt asked. “Those ought to be known to the general public.”

Some conservation groups are looking into whether it makes sense to advocate for a plan that caps levels in Lake Powell somewhere below its full capacity to protect those resources.

“There are few things worse than losing a special place the first time but one of them is losing it a second time,” said Mike Fiebig, director of Southwest River Protection at American Rivers.

With both Lake Powell and Lake Mead hovering around a third of capacity and long-term drought predicted to continue by leading climate models for the basin, Fiebig said recovering riparian ecosystems and emerging cultural sites in the bed of Lake Powell need to be taken into account as water managers decide which reservoirs to fill first.

The water crisis that emerged in the Colorado Basin this year, when spring runoff largely failed to materialize, prompted the Bureau of Reclamation to repeatedly revise its projections to accommodate dropping levels in Lake Powell. The latest report, which was released last month, acknowledges that the Glen Canyon Dam may be unable to generate power as soon as next year.

Fiebig believes the water supply challenges could make previously ossified political assumptions more fluid.

“If we didn’t have the threat of collapse,” he said, “we probably wouldn’t have the opportunity to change things for the better.”

The Glen Canyon Institute, which has advocated for the decommissioning of the Glen Canyon Dam since the group’s founding in 1996, sees the potential to bring ideas to the table that were once dismissed by water managers as radical.

The institute has long pushed a proposal to prioritize storage in Lake Mead over Lake Powell, which Scott Christensen, a board member for the Glen Canyon Institute and executive director of Greater Yellowstone Coalition, said makes sense from both the water management and conservation perspectives.

Given climate change and increasing demand for water in the Southwest, he said, “it makes less and less sense to have two massive reservoirs in the middle of the desert.” Efforts to prop up Lake Powell by draining upper-elevation reservoirs — a strategy that began this year — will only delay the inevitable, he added.

“Water shortages are no longer theoretical,” Christensen said. “It’s real. It’s happening now, and people who depend on this watershed and who care about this river and these landscapes need to understand what’s happening here.”

The ‘Dominy Formation’

When the science circus pulled into the mouth of Dark Canyon on the second to last day of the trip, everyone was talking about the so-called “Dominy Formation” — an informal name for the reservoir sediment that nods to the controversial former commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation and prime mover behind Lake Powell and many other dam projects, Floyd Dominy.

Accessing the bottom of Dark Canyon from the Colorado had been a difficult prospect for years, its lower miles mired in muck and confined to a narrow, tumbleweed-filled trench.

As recently as early August, the trench through the sediment emptied into a 50-foot deep river pool. After a series of powerful monsoon storms in the late summer, however, the canyon was completely transformed. Flash floods blasted sediment into the river, exposing the canyon bottom’s original bedrock and widening the trench from 10 to 60 feet in spots. The deep river pool had completely filled in with mud.

Cari Johnson, a geology professor at the University of Utah, analyzed Dominy Formation beds in Waterhole Canyon on a trip last year. She was planning to do more work exploring how the deposits formed, but after seeing the changes in Dark Canyon and elsewhere, she realized she’d need to expand the scope of her project to include erosion as well as deposition.

“It’s not eroding in the way that I thought it would,” she said. “We could literally come back after one big storm and find something totally different.”

Being caught off guard by the speed of transformation in the area is a common refrain from those who visit Lake Powell often, whether they’re cheering on the return of the river or mourning the loss of the redrock reservoir.

Essayist and Pulitzer Prize finalist Ellen Meloy wrote in 1995 about traveling across a nearly full Lake Powell amid waterlogged sofas and “Dorito-addicted carp.”

“For conservationists,” she wrote, “Glen Canyon Dam was an act of gross vandalism. For others it is a monument to progress and human ingenuity, a recreation paradise, and economic boon, and for its energy supply, a necessity.”

A quarter century later, the dam is still seen as all of these things. But the reservoir behind it — in spite of, or perhaps because of, the exuberance of human ingenuity — is disappearing.

—— Several of the interviews used in this story were conducted in conjunction with Sam Carter’s River Radius podcast.

Zak Podmore is a Report for America corps member and writes about conflict and change in San Juan County for The Salt Lake Tribune. Your donation to match our RFA grant helps keep him writing stories like this one; please consider making a tax-deductible gift of any amount today by clicking here.